The “Ames houring” dataset, part of a Kaggle competition, is an extended and more modern version of the Boston housing datasets. It presents 81 features of houses – mostly single family suburban dwellings – that were sold in Ames, Iowa in the period 2006-2010, which encompasses the housing crisis. Compared to the Boston dataset, it is more complex to handle, with missing data and both categorical and numerical features.

The goal is to build a machine learning model to predict the selling price for the home, and in the process learn something about what makes a home worth more or less to buyers. Since the housing market isn’t particularly hard to understand, the most important features are not difficult to guess: overall size, number of room, quality of the house, neighborhood, the overall economy, and we should be able to see this in the data using a simple regression model, which we do in this first part. In this second part of this port we’ll explore more sophisticated models.

from datetime import datetime

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

import matplotlib.ticker as tkr

import numpy as np

import pandas as pd

import seaborn as sns

df = pd.read_csv('./ames-dataset-orig.csv', sep='\t')

df.drop(['Order', 'PID'], axis=1, inplace=True)

df = df.replace(['NA', ''], np.NaN)

print(f"The dataset contains {len(df)} rows and {len(df.keys())} columns")

print(f"The dataset contains {df.isna().sum().sum()} NAs.")

The dataset contains 2930 rows and 80 columns

The dataset contains 13997 NAs.

numeric = [k for k in df.keys() if k not in df.select_dtypes("object").keys()]

df[numeric] = df[numeric].astype('float')

It is easier to work with column names without spaces, so we remove them.

df.columns = df.columns.str.replace(' ', '')

A quick look at the first lines shows all the columns.

df.head()

| MSSubClass | MSZoning | LotFrontage | LotArea | Street | Alley | LotShape | LandContour | Utilities | LotConfig | ... | PoolArea | PoolQC | Fence | MiscFeature | MiscVal | MoSold | YrSold | SaleType | SaleCondition | SalePrice | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 20.0 | RL | 141.0 | 31770.0 | Pave | NaN | IR1 | Lvl | AllPub | Corner | ... | 0.0 | NaN | NaN | NaN | 0.0 | 5.0 | 2010.0 | WD | Normal | 215000.0 |

| 1 | 20.0 | RH | 80.0 | 11622.0 | Pave | NaN | Reg | Lvl | AllPub | Inside | ... | 0.0 | NaN | MnPrv | NaN | 0.0 | 6.0 | 2010.0 | WD | Normal | 105000.0 |

| 2 | 20.0 | RL | 81.0 | 14267.0 | Pave | NaN | IR1 | Lvl | AllPub | Corner | ... | 0.0 | NaN | NaN | Gar2 | 12500.0 | 6.0 | 2010.0 | WD | Normal | 172000.0 |

| 3 | 20.0 | RL | 93.0 | 11160.0 | Pave | NaN | Reg | Lvl | AllPub | Corner | ... | 0.0 | NaN | NaN | NaN | 0.0 | 4.0 | 2010.0 | WD | Normal | 244000.0 |

| 4 | 60.0 | RL | 74.0 | 13830.0 | Pave | NaN | IR1 | Lvl | AllPub | Inside | ... | 0.0 | NaN | MnPrv | NaN | 0.0 | 3.0 | 2010.0 | WD | Normal | 189900.0 |

5 rows × 80 columns

It is absolutely important to understand what the columns represent. The best description of the dataset is in the description provided by the dataset’s author, which is worth a read. Let’s check the number of non-null elements in each columns.

df.info()

<class 'pandas.core.frame.DataFrame'>

RangeIndex: 2930 entries, 0 to 2929

Data columns (total 80 columns):

# Column Non-Null Count Dtype

--- ------ -------------- -----

0 MSSubClass 2930 non-null float64

1 MSZoning 2930 non-null object

2 LotFrontage 2440 non-null float64

3 LotArea 2930 non-null float64

4 Street 2930 non-null object

5 Alley 198 non-null object

6 LotShape 2930 non-null object

7 LandContour 2930 non-null object

8 Utilities 2930 non-null object

9 LotConfig 2930 non-null object

10 LandSlope 2930 non-null object

11 Neighborhood 2930 non-null object

12 Condition1 2930 non-null object

13 Condition2 2930 non-null object

14 BldgType 2930 non-null object

15 HouseStyle 2930 non-null object

16 OverallQual 2930 non-null float64

17 OverallCond 2930 non-null float64

18 YearBuilt 2930 non-null float64

19 YearRemod/Add 2930 non-null float64

20 RoofStyle 2930 non-null object

21 RoofMatl 2930 non-null object

22 Exterior1st 2930 non-null object

23 Exterior2nd 2930 non-null object

24 MasVnrType 2907 non-null object

25 MasVnrArea 2907 non-null float64

26 ExterQual 2930 non-null object

27 ExterCond 2930 non-null object

28 Foundation 2930 non-null object

29 BsmtQual 2850 non-null object

30 BsmtCond 2850 non-null object

31 BsmtExposure 2847 non-null object

32 BsmtFinType1 2850 non-null object

33 BsmtFinSF1 2929 non-null float64

34 BsmtFinType2 2849 non-null object

35 BsmtFinSF2 2929 non-null float64

36 BsmtUnfSF 2929 non-null float64

37 TotalBsmtSF 2929 non-null float64

38 Heating 2930 non-null object

39 HeatingQC 2930 non-null object

40 CentralAir 2930 non-null object

41 Electrical 2929 non-null object

42 1stFlrSF 2930 non-null float64

43 2ndFlrSF 2930 non-null float64

44 LowQualFinSF 2930 non-null float64

45 GrLivArea 2930 non-null float64

46 BsmtFullBath 2928 non-null float64

47 BsmtHalfBath 2928 non-null float64

48 FullBath 2930 non-null float64

49 HalfBath 2930 non-null float64

50 BedroomAbvGr 2930 non-null float64

51 KitchenAbvGr 2930 non-null float64

52 KitchenQual 2930 non-null object

53 TotRmsAbvGrd 2930 non-null float64

54 Functional 2930 non-null object

55 Fireplaces 2930 non-null float64

56 FireplaceQu 1508 non-null object

57 GarageType 2773 non-null object

58 GarageYrBlt 2771 non-null float64

59 GarageFinish 2771 non-null object

60 GarageCars 2929 non-null float64

61 GarageArea 2929 non-null float64

62 GarageQual 2771 non-null object

63 GarageCond 2771 non-null object

64 PavedDrive 2930 non-null object

65 WoodDeckSF 2930 non-null float64

66 OpenPorchSF 2930 non-null float64

67 EnclosedPorch 2930 non-null float64

68 3SsnPorch 2930 non-null float64

69 ScreenPorch 2930 non-null float64

70 PoolArea 2930 non-null float64

71 PoolQC 13 non-null object

72 Fence 572 non-null object

73 MiscFeature 106 non-null object

74 MiscVal 2930 non-null float64

75 MoSold 2930 non-null float64

76 YrSold 2930 non-null float64

77 SaleType 2930 non-null object

78 SaleCondition 2930 non-null object

79 SalePrice 2930 non-null float64

dtypes: float64(37), object(43)

memory usage: 1.8+ MB

By inspecting the output of describe(), we see that three columns have less than 300 non-null entries. Such columns have little explanatory power, so it is better to remove them.

df.drop(['Alley', 'PoolQC', 'MiscFeature'], axis=1, inplace=True)

print(f"Kept {len(df.keys())} columns.")

Kept 77 columns.

We have quite a lot of missing data, with Alley, FireplaceQu, PoolQC, Fence, MiscFeature almost empty, and a few others, like LotFrontage for example, that have a handful of null values. Later on we’ll see how to deal with such cases. We also need to remove all data with MSZoning defined as commercial, agriculture and industrial as these are not residential units.

condition = (df.MSZoning != 'C (all)') & (df.MSZoning != 'I (all)') & (df.MSZoning != 'A (agr)')

df = df[condition]

df['MSZoning'].value_counts()

RL 2273

RM 462

FV 139

RH 27

Name: MSZoning, dtype: int64

And now let’s look at the features in more details. The last column is SalePrice, which is the target we would like to predict, and is numerical. For the remaining columns, we have both numerical and categorical features, roughly in the same proportion. For the time being we keep both features and target in the same dataset, as we want to find to which features the target is correlated. We still take out the SalePrice column when we define the numerical features.

target_name = "SalePrice"

numerical_features = df.drop(columns=target_name).select_dtypes("number")

numerical_features = numerical_features[numerical_features.keys()]

print(f"# numerical features: {len(numerical_features.keys())}")

string_features = df.select_dtypes(object)

print(f"# categorical features: {len(string_features.keys())}")

# numerical features: 36

# categorical features: 40

Let’s start plotting from the categorical features.

from math import ceil

from itertools import zip_longest

n_string_features = string_features.shape[1]

nrows, ncols = ceil(n_string_features / 4), 4

fig, axs = plt.subplots(ncols=ncols, nrows=nrows, figsize=(14, 80))

for feature_name, ax in zip_longest(string_features, axs.ravel()):

if feature_name is None:

# do not show the axis

ax.axis("off")

continue

string_features[feature_name].value_counts().plot.barh(ax=ax)

ax.set_title(feature_name)

plt.subplots_adjust(hspace=0.2, wspace=0.8)

For quite a few features (for example, Electrical, Heating', 'Condition1', 'Condition2', GarageQual', 'GarageCond, Pavedrive) one category contains almost all the data, so the information they provide is small and we will ignore them.

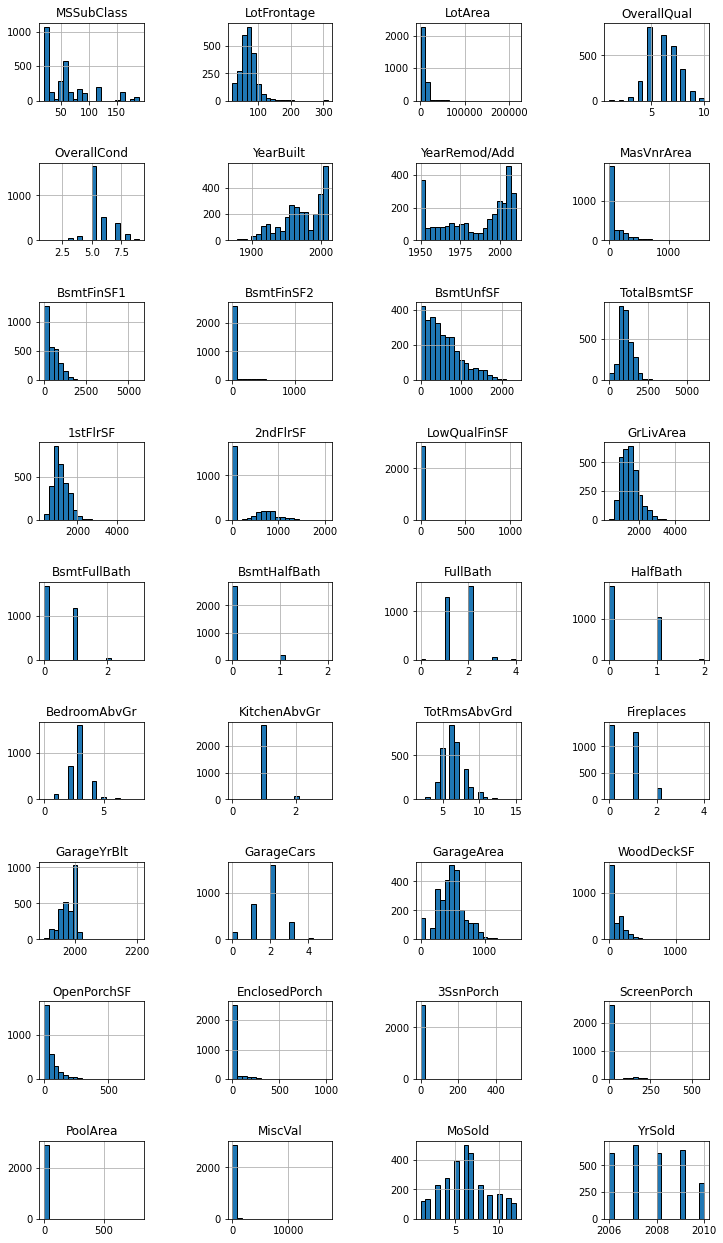

And now the numerical features by plotting their histograms.

numerical_features.hist(bins=20, figsize=(12, 22), edgecolor="black", layout=(9, 4))

plt.subplots_adjust(hspace=0.8, wspace=0.8)

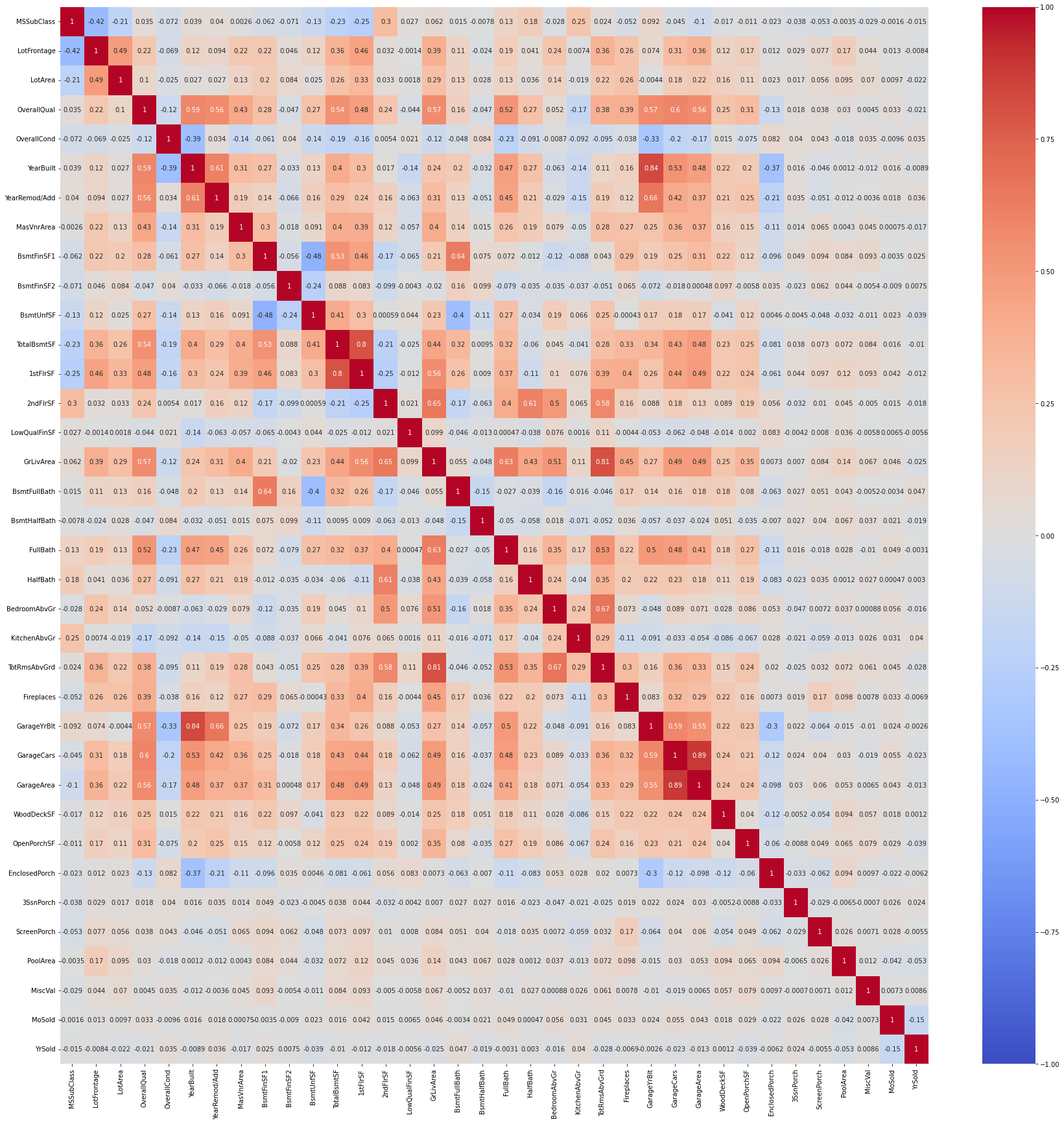

Now we look at the correlation among numerical features.

corr = numerical_features.corr()

fig = plt.figure(figsize=(30, 30))

sns.heatmap(corr, cmap="coolwarm", vmin=-1, vmax=1, annot=True);

The heatmap contains lots of numbers and it is not easy to distinguish the wheat from the chaff. A simple loop over the correlation matrix reports the most important correlations.

for label, row in corr.iterrows():

row = row[row.abs() > 0.6].dropna()

if len(row) <= 1: continue

print(label, end=':')

for k, v in row.iteritems():

if k == label: continue

print(f' {k} ({v:.2%})', end='')

print()

YearBuilt: YearRemod/Add (60.95%) GarageYrBlt (83.54%)

YearRemod/Add: YearBuilt (60.95%) GarageYrBlt (65.63%)

BsmtFinSF1: BsmtFullBath (63.94%)

TotalBsmtSF: 1stFlrSF (80.23%)

1stFlrSF: TotalBsmtSF (80.23%)

2ndFlrSF: GrLivArea (65.48%) HalfBath (61.36%)

GrLivArea: 2ndFlrSF (65.48%) FullBath (62.78%) TotRmsAbvGrd (80.70%)

BsmtFullBath: BsmtFinSF1 (63.94%)

FullBath: GrLivArea (62.78%)

HalfBath: 2ndFlrSF (61.36%)

BedroomAbvGr: TotRmsAbvGrd (67.11%)

TotRmsAbvGrd: GrLivArea (80.70%) BedroomAbvGr (67.11%)

GarageYrBlt: YearBuilt (83.54%) YearRemod/Add (65.63%)

GarageCars: GarageArea (88.82%)

GarageArea: GarageCars (88.82%)

The number of cars in the garage, as well as the size of the garage, are heavily correlated with the overall quality of the house. The built or renovation year for the house in unsurprisingly correlated with the renovation of built year for the garage. The area of the different sizes of the house are correlated as expected as well, as it is unusual to find a very large bathroom in a small house, or viceversa. The area of the first floor is heavily correlated with that of the basement, which makes sense from a typical construction.

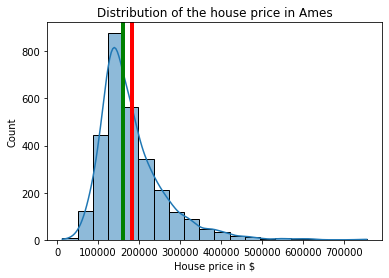

It is time to look at a plot of the target distribution.

sns.histplot(df, x="SalePrice", bins=20, kde=True)

plt.xlabel("House price in $")

plt.axvline(x=df['SalePrice'].mean(), linewidth=4, color='red')

plt.axvline(x=df['SalePrice'].median(), linewidth=4, color='green')

_ = plt.title("Distribution of the house price in Ames")

Clearly, house prices are only positive, with a long tail that stretched four times the mean value. Only a few houses have large prices though.

print(f"# prices < 500K: {sum(df['SalePrice'] <= 500_000)}, # prices above 500K: {sum(df['SalePrice'] > 500_000)}")

# prices < 500K: 2884, # prices above 500K: 17

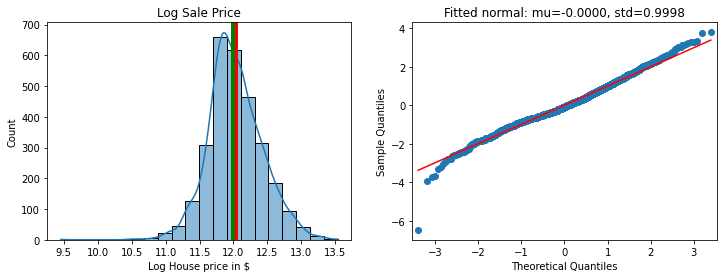

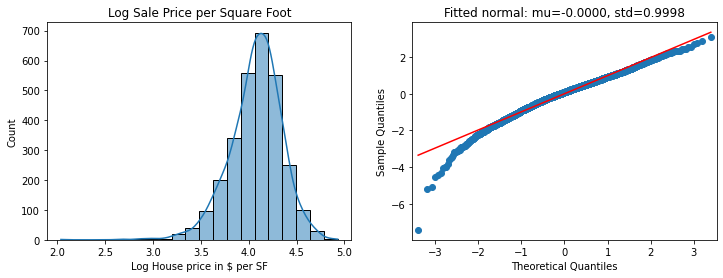

The logarithm of the sale price is quite close to a normal distribution, meaning that the sale price itself is lognormal. The Q-Q plot shows some outliers, especially for low prices, but it otherwise quite close to that of a standard normal. This means that linear regression models should work nicely.

from scipy.stats import norm

import statsmodels.api as sm

df['LogSalePrice'] = np.log(df['SalePrice'])

df['ScaledLogSalePrice'] = \

(df['LogSalePrice'] - df['LogSalePrice'].mean()) / df['LogSalePrice'].std()

mu, std = norm.fit(df['ScaledLogSalePrice'])

fig, (ax0, ax1) = plt.subplots(figsize=(12, 4), ncols=2)

sns.histplot(df, x="LogSalePrice", bins=20, kde=True, ax=ax0)

ax0.set_xlabel("Log House price in $")

ax0.axvline(x=df['LogSalePrice'].mean(), linewidth=4, color='red')

ax0.axvline(x=df['LogSalePrice'].median(), linewidth=4, color='green')

ax0.set_title('Log Sale Price')

_ = sm.qqplot(df['ScaledLogSalePrice'], line='r', ax=ax1)

ax1.set_title(f"Fitted normal: mu={mu:.4f}, std={std:.4f}");

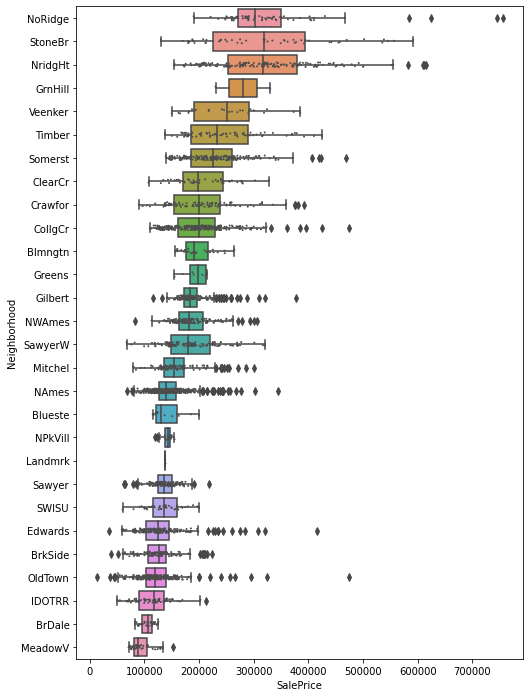

The point at -6 standard deviations is an outliner, with and Abnormal SaleCondition. Most of entries with ScaledLogSalePrice are in the same neighborhood, OldTown, with another few in Edwards and IDOTTR. As the boxplot below shows, OldTown has wide variations in the sale price, with a lowest value of about $12,000 and the highest of $450,000. Incidentally, this shows that the neighborhood feature is an important one. After all, one of the mantras of real estate is “location, location, location”, therefore we expect the neighborhood to be important. It is not clear how to use this variable though, as there are 28 different neighborhoods in the dataset and no obvious way to create a numerical variable out of them.

order = df.groupby('Neighborhood')['SalePrice'].mean().sort_values(ascending=False).index

fig = plt.figure(figsize=(8, 12))

sns.boxplot(data=df, x='SalePrice', y='Neighborhood', order=order)

sns.stripplot(data=df, x='SalePrice', y='Neighborhood', order=order,

size=2, color=".3", linewidth=0)

<AxesSubplot:xlabel='SalePrice', ylabel='Neighborhood'>

A valuable alternative for the target is the price per square foot, which is often requested when looking for new houses. We plot it and compare with the sale price itself.

df['TotalLivArea'] = df['GrLivArea'] + df['1stFlrSF'] + df['2ndFlrSF']

df['SalePriceSF'] = df['SalePrice'] / df['TotalLivArea']

df['LogSalePriceSF'] = np.log(df['SalePriceSF'])

df['ScaledLogSalePriceSF'] = \

(df['LogSalePriceSF'] - df['LogSalePriceSF'].mean()) / df['LogSalePriceSF'].std()

mu, std = norm.fit(df['ScaledLogSalePriceSF'])

fig, (ax0, ax1) = plt.subplots(figsize=(12, 4), ncols=2)

sns.histplot(df, x="LogSalePriceSF", bins=20, kde=True, ax=ax0)

ax0.set_xlabel("Log House price in $ per SF")

ax0.set_title('Log Sale Price per Square Foot')

_ = sm.qqplot(df['ScaledLogSalePriceSF'], line='r', ax=ax1)

ax1.set_title(f"Fitted normal: mu={mu:.4f}, std={std:.4f}");

The difference isn’t massive, but SalePrice looks a tad better, so we’ll stick with that.

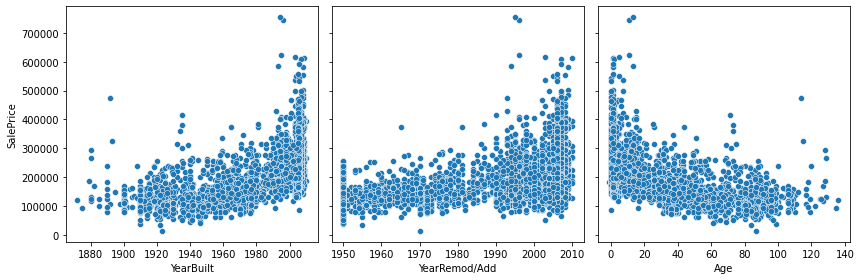

And now the difficult part – trying to find important relationships between the features and the target. By common sense we expect the sale price to be correlated with the year in which the house was built or last renovated; correlated with the lot area; correlated with the total house area; correlated with the number of rooms. We expect some dependency on the time of the transaction, with an effect from the 2008 crisis. Let’s explore each point.

The age of the house, defined above as the number of years from when the house was built or last renovated. The Age feature we built above puts together YearBuilt and YearRemod/Add and shows what we expect: more modern houses are worth more than old houses. We will drop YearBuilt and YearRemod/Add and only use Age.

age = df.apply(lambda x: x['YrSold'] - x['YearBuilt'] \

if x['YearBuilt'] < x['YearRemod/Add']

else x['YrSold'] - x['YearRemod/Add'], axis=1)

age.name = 'Age'

df['Age'] = age

fig, (ax0, ax1, ax2) = plt.subplots(figsize=(12, 4), ncols=3, sharey=True)

sns.scatterplot(data=df, x="YearBuilt", y="SalePrice", ax=ax0)

sns.scatterplot(data=df, x="YearRemod/Add", y="SalePrice", ax=ax1)

sns.scatterplot(data=df, x="Age", y="SalePrice", ax=ax2)

fig.tight_layout()

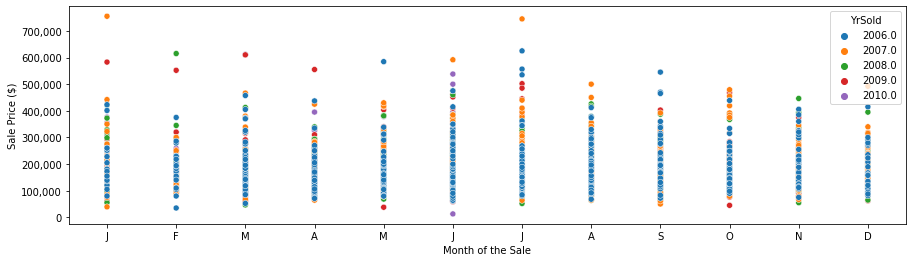

Plotting the sales price as a function of the month of the sale shows a little dependency, with large lages in January and July, surprising low prices in February, and slightly higher prices in March and April, followed by lower prices in December. The largest values are in 2007 (before the 2008 crisis), but we see large sale prices also for the period following the 2008 crisis.

fig, ax = plt.subplots(figsize=[15, 4])

sns.scatterplot(data=df, x='MoSold', y='SalePrice', hue='YrSold', palette='tab10')

plt.xticks([1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12],

['J', 'F', 'M', 'A', 'M', 'J', 'J', 'A', 'S', 'O', 'N', 'D'])

plt.xlabel('Month of the Sale')

plt.ylabel('Sale Price ($)')

ax.get_yaxis().set_major_formatter(tkr.FuncFormatter(lambda x, p: f'{int(x):,d}'))

sale_dates = df[['YrSold', 'MoSold']].apply(

lambda x: datetime(year=int(x['YrSold']), month=int(x['MoSold']), day=1), axis=1)

df['Sale Date'] = sale_dates

fig, ax = plt.subplots(figsize=[15, 4])

sns.scatterplot(data=df, x='Sale Date', y='SalePrice', hue='OverallQual', palette='tab10')

plt.xlabel('Sale Date')

plt.ylabel('Sale Price')

ax.get_yaxis().set_major_formatter(tkr.FuncFormatter(lambda x, p: format(int(x), ',')))

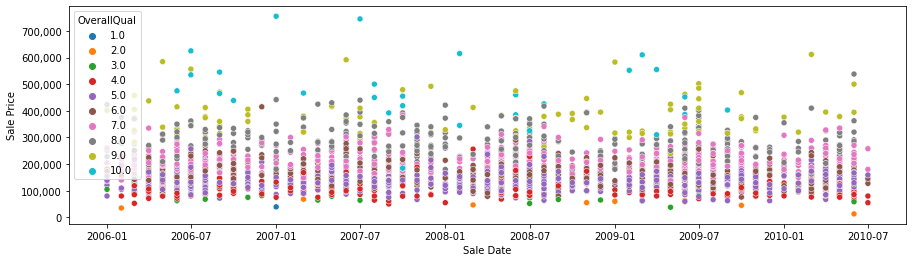

The highest sale prices (around 700,000) are recorded before the 2008 crisis; after 2008 the highest sale prices are much lower (between 500,000 and 600,000). So the 2008 crisis has a clear effect on the few transactions on the high side; for the majority of the sales it is less clear from the graph above. It is also obvious (and expected) that the overall quality of the house is quite important to determine the price.

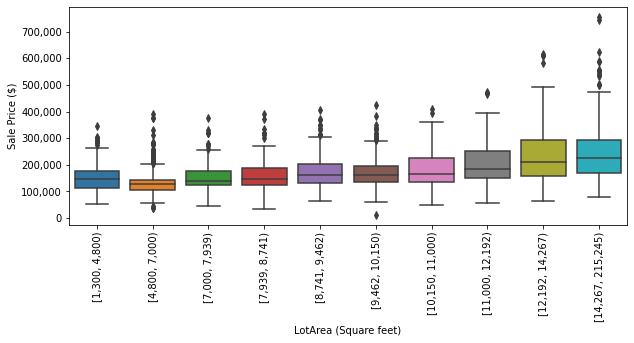

Another feature that should play an important role in the sale price is the lot area. We first create ten bins and show the boxplots for each of them. The bins are defined using the 0%-quantile, 10%-quantile, and so on up to the 100%-quantile.

quantiles = df['LotArea'].quantile(np.linspace(0, 1, 11)).values

quantiles = list(map(int, quantiles))

df['LotArea Bin'] = pd.cut(df['LotArea'], quantiles)

fig, ax = plt.subplots(figsize=(10, 4))

sns.boxplot(data=df, x="LotArea Bin", y="SalePrice", ax=ax)

plt.xlabel('LotArea (Square feet)')

plt.ylabel('Sale Price ($)')

ax.set_xticklabels([f'[{quantiles[i]:,d}, {quantiles[i + 1]:,d})' for i in range(10)], rotation=90)

ax.get_yaxis().set_major_formatter(tkr.FuncFormatter(lambda x, p: format(int(x), ',')))

All the highest prices are in the 80%-to-100% quantiles and overall the mean price per quantile increases with the lot area; we can notice several outliers though. The mean of the second bin is smaller, and with less dispersion, than the one of the first bin, which is a bit unexpected.

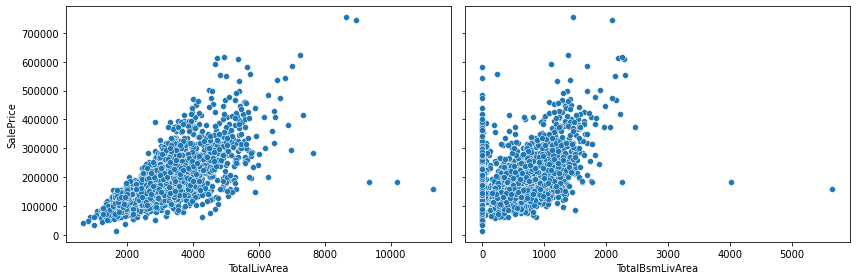

To reduce the number of features, we sum GrLivArea, 1stFlrSF and 2ndFlrSF into a single total living area, and we subtract BsmtUnfSF from TotalBsmtSF to define the finished basement area. The two new features are both positively correlated with the sale price, albeit with a few outliers.

df['TotalLivArea'] = df['GrLivArea'] + df['1stFlrSF'] + df['2ndFlrSF']

df['TotalBsmLivArea'] = df['TotalBsmtSF'] - df['BsmtUnfSF']

fig, (ax0, ax1) = plt.subplots(figsize=(12, 4), ncols=2, sharey=True)

sns.scatterplot(data=df, x="TotalLivArea", y="SalePrice", ax=ax0)

sns.scatterplot(data=df, x="TotalBsmLivArea", y="SalePrice", ax=ax1)

fig.tight_layout()

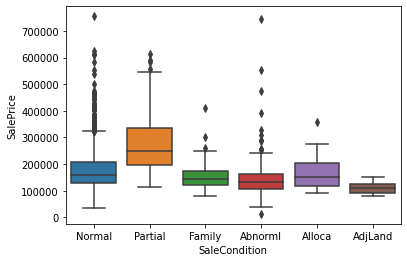

Another interesting feature is SaleCondition. Most of the sales are in the Normal category; quite a few are Partial, which from the description file means that the house was not completed, and Abnorml, that is trade, foreclosure, or short sale. Perhaps it is not a surprise that Partial houses are more expensive as they are new houses. Family and AdjLand tend to be a tad cheaper, and this is a bit expected as well and intra-family sales may be for out-of-the-market prices.

for k, v in df['SaleCondition'].value_counts().items():

print(f'{k:8s}: {v:4d} entries ({v / len(df):4.1%})')

sns.boxplot(data=df, x='SaleCondition', y='SalePrice');

Normal : 2397 entries (82.6%)

Partial : 245 entries (8.4%)

Abnorml : 179 entries (6.2%)

Family : 46 entries (1.6%)

Alloca : 22 entries (0.8%)

AdjLand : 12 entries (0.4%)

This concludes the exploratory data analysis. In Part II we will fit a linear regression model.